Adaptation

Beware of the pool, blue bottomless pool

It leads you straight right through the gate that opens on the pool

There I was at midnight, tired but not tired. After weeks of feeling stuck with a story, I’d decided to drop it entirely and go back to another piece in progress. ‘There’s a good story here,’ I told myself as I closed the notebook, ‘but forcing it because you feel you have to write something, will make it disingenuous.’As I put all the research books away, I felt a tiny weight lift off my shoulders, and from this lightness a sort of portal opened. By relieving myself of the pressure, I’d squirreled a path to my creativity that for weeks had felt blocked off. What was I to do now? Anything I wanted. That’s how at midnight, with the required bandwidth afforded me, I watched a serious film.

Keep off the path, beware of the gate

Watch out for signs that say ‘hidden pathways’

This year one of my artistic endeavours is to read and watch as many book to film adaptations as I can handle. As a writer, it’s important I keep my muscles strong and build new ones. I’m never going to graduate school, so those in-depth courses where one spends weeks learning how to write fill-in-the-blank, I’ll have to do on my own. How a book adapts into a good movie is an area that particularly excites me. The high school English teacher that got me hooked, would say that not all great books make great movies and sometimes bad books make great films. Mr. Seel was right. A lot of great literature has had a tough go on the silver screen (unless you’re talking about James Cain, Stephen King or Elmore Leonard,their work was made for the screen). The one film that comes to mind is The Great Gatsby. I don’t like the book yet I recognise it as being part of the American canon. But from Robert Redford to Leonardo DiCaprio, that book has never hit the right chord on film. Why is it? It’s got all the necessary components for a great film: glitz, rags-to-riches, death, intrigue. So, what’s the celluloid problem? Well, that’s the secret sauce I’ll try to uncover in2026.

Walkin’ through the gate that leads you down

Down to a pool fraught with danger, it’s a pool full of strangers

I did it, I finally watched Gus Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho. I didn’t know what to expect, which is strange since literally every film buff has something to say about this film. I figured I’d watch it in two sittings (it was midnight after all and I’m old and can’t seem to finish a viewing in a night), no big deal, and then River Phoenix knocked off on the road. If taping my eyelids back was what I’d resort to, I was going to watch this piece to the end.

I’m a classically trained actor (whoopdy doo), and as such I have an ear for iambic pentameter. It was with great pleasure to note that I still had it when somewhere in the midst of Mike and Scott falling asleep to them rising on rooftops,their language changed. And how incredibly chuffed I was to note that the text being quoted was from none other than Shakespeare’s Henry plays— specifically the IV part I and II, I spent a couple of nearly bored to death months slaving over. After the initial excitement, I admit my enthusiasm waned. Firstly, the heartbeat rhythm of the text was constantly getting muffled by actor’s who weren’t familiar with it. Second, I couldn’t understand what the point of putting Shakespeare in the middle of John Rechy’s adapted novel City of Light.Was Van Sant trying to give the hustlers respectability by having them verbally spar in heightened language? Or was he simply trying to add a little artistic flair to a story that needed a suitable antagonists arc? I don’t know, but it became annoying the more Bill Shakes word’s poetry got butchered.

I have not read Rechy’s book, so though it’s lauded, I cannot comment as to how the source material differs from the film. What I can say is My Own Private Idaho is some kind of film, one that’s mightily carried by River Phoenix. To label it queer cinema is to take away it’s right to being on the shelf of great films. The story of this young hustler and his search for his mother—and really himself—is so poignantly told that you forgive the terrible Shakespeare. Hookers with hearts of gold are Hollywood’s favourite trope, and contrite they too often are, but this film, this little budget gem of an imperfect masterpiece made me care about this boy and his crew of lost boys in a way I haven’t for fictional characters. Once Scotty stopped embarrassing Falstaff, I mean Bob, I was relieved to see the boys on the road again, searching for what was, could be and became.The ending was, well an ending. One that didn’t bring closure for anyone, for as the credits closed every character still longed for the same thing they did in the first frame.

Hey! You’re living in your own private Idaho

Where do I go from here to a better state than this?

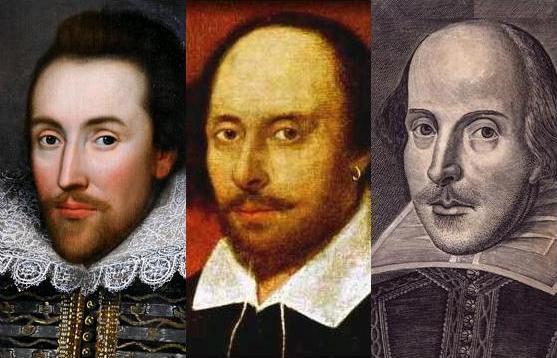

Image: Shakespeare's Portraits by Cobbe, Chandos and Droeshout

Song Lyrics: Private Idaho by the B-52's